Tuesday’s news that a ransomware infection shut down a US pipeline operator for two days has generated no shortage of questions, not to mention a near-endless stream of tweets.

Some observers and arm-chair incident responders consider the event to be extremely serious. That’s because the debilitating malware spread from the unnamed company’s IT network—where email, accounting, and other business is conducted—to the company’s operational technology, or OT, network, which automatically monitors and controls critical operations carried out by physical equipment that can create catastrophic accidents when things go wrong.Others said the reaction to the incident was overblown. They noted that, per the advisory issued on Tuesday, the threat actor never obtained the ability to control or manipulate operations, that the plant never lost control of its operations, and that facility engineers deliberately shut down operations in a controlled manner. This latter group also cited evidence that the infection of the plant’s industrial control systems, or ICS, network appeared to be unintentional on the part of the attackers.

Assessing the threat that the event posed to public safety requires an understanding of ICS and the way ransomware infections have evolved. What follows are answers to some of the most frequently asked questions:

What happened?

Details are frustratingly scarce. According to an advisory published by the US Department of Homeland Security’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, or CISA, the ransomware infected an unnamed natural gas compression facility. The attack started with a malicious link in a phishing email that allowed attackers to obtain initial access to the organization’s information technology (IT) network and later pivot to the company’s OT network. Eventually, both the IT and OT networks were infected with what the advisory described as “commodity ransomware.”

The infection of the OT network caused engineers to lose access to several automated resources that read and aggregate real-time operational data from equipment inside the facility’s compression operations. These resources included human machine interfaces, or HMIs, data historians, and polling servers. The loss of these resources resulted in a partial “loss of view” for engineers.

Facility personnel responded by implementing a “deliberate and controlled shutdown to operations” that lasted about two days. Compression facilities in other geographic locations that were connected to the hacked facility were also shut down, causing the entire pipeline to be nonoperational for two days. Normal operations resumed after that.

What’s a natural gas compression facility and what do they do?

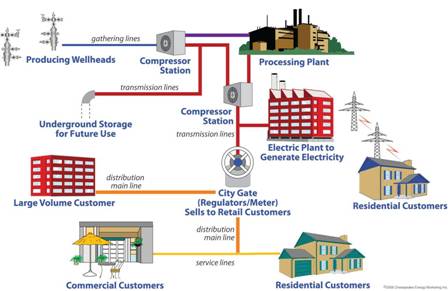

Before natural gas can be moved through interstate pipelines, it must be highly pressurized at periodic intervals along the way. This process is done by compression facilities, which are typically spaced 40 to 100 miles apart along the pipeline. Natural gas flows into the compression facility, which is also known as a compressor station or a pumping station, where the gas is compressed by a turbine, motor, or engine. For more, see this link.

What’s a data historian?

Also known as an operational historian, it’s a database that keeps a historical record of values related to industrial processes. Values include temperatures, pressures, and voltage, to name just a few. Engineers use data historians to track data, anticipate equipment failures and maintenance requirements, and estimate future output. See more here.

What’s an HMI?

An HMI is an interface that uses visual, textual and auditory information. Plant operators use HMIs to send commands to the control systems that in turn control physical processes. More available here.

What’s a loss of view?

It occurs when plant operators can no longer see what's happening in the control system as a result of an equipment failure or a cyber attack.

What do we know about the infected facility?

Very little, because law enforcement and security officials consider such details highly sensitive. Consequently, Tuesday’s CISA advisory didn’t identify the facility. However, a post published on Wednesday by industrial cybersecurity firm Dragos assesses with high confidence that the cyber attack CISA reported is the same one the US Coast Guard reported in December. The Coast Guard bulletin didn’t name the facility either, but it did say the attack infected a facility that’s regulated by a law known as the Maritime Transportation Security Act, which applies to most tankers, barges, and other vessels involved in the production and transfer of natural gas. That suggests the facility may be located near a major port or waterway.

What do we know about the attack? How did it go down?

Again, we know very little. Both the Coast Guard and CISA said that the initial point of entry was a malicious link embedded in a spam email. That suggests that an employee, contractor, or other person connected to the facility followed the link and got infected. From there, the infection spread to the IT network, and eventually to the OT network, where the facility’s ICS is hosted. Eventually, files in both the IT and OT networks were encrypted.

Both reports said the compromise spread to the ICS assets was aided by a lack of adequate segmentation between the facility’s IT and OT networks. Best practices call for there to be major boundaries between these two networks to prevent precisely the kind of pivoting described in the reports.

Multiple ICS security experts said that in practice, many facilities take shortcuts when erecting these defenses. One of the main reasons for this is efficiency. Strict segmentation would likely require having an operator at every substation and forgo connecting any equipment over public networks. That would drive up costs. In any event, this lack of segmentation made it possible for attackers to use their access to the IT network to fan out to the OT network.

Phishing? Really?

Yep, phishing remains one of the most effective ways to get into most networks.

Are there other examples of critical infrastructure facilities having their OT networks infected?

Yes. One of the best-known examples is the 2003 infection of Ohio's Davis-Besse nuclear power plant by the virulent Windows worm known as Slammer. The worm entered the facility’s IT network through a contractor’s computer that was connected over a T1 connection. Because the T1 connection bypassed a firewall that blocked the IP port Slammer used to spread, it was able to take hold inside the facility’s corporate network.

Eventually, Slammer spread to the OT network. Fortunately, there was no physical damage. After a hole was found in the plant's reactor head, the nuclear power plant had been taken offline in 2002.

Other examples of malware that traversed IT/OT network boundaries include Indestroyer, Trisis,

WannaCry, and NotPetya.

Lesley Carhart, principal industrial incident responder at Dragos, said unintentional infections “aren’t uncommon in industrial environments, due to devices like USB drives, laptops, or cellular modems moving in and out of facility computer networks.”

What’s known about the ransomware that infected the natural gas facility?

CISA described the malware as “commodity ransomware.” The Coast Guard identified the malware as Ryuk, one of the most prolific strains of malware that has crippled networks belonging to the state of Georgia’s court system and several major state agencies in Louisiana, to name just two victims.

Is that really all the publicly available information about the attack?

Pretty much, yes. In the absence of details, ICS security experts have speculated how the attack may have played out. Based on the typical techniques used by ransomware attackers, Dragos researchers believe the attackers used their initial access to obtain login credentials to access, or otherwise compromise, the network’s active directory.

An active directory is a set of services and processes included in Microsoft Windows server operating systems. It’s responsible for a variety of highly sensitive tasks. Logging in users, running scripts that configure users’ computers and assign system privileges, and controlling what network resources are available to various users or groups are just a few of the tasks an active directory carries out.

With the likely compromise of the active directory, Dragos said, the attackers would have been able to infect virtually every Windows-based system connected to the network. Because of the lack of segmentation, that would include the OT network.

Was the infection of the OT network really unintentional?

It depends on who you ask. Dragos said that available evidence doesn’t indicate that the adversaries specifically targeted OT operations. Dragos also said that “the events in the CISA alert represent well-known ransomware behavior and is not an ICS-specific or ICS targeted event.”

Two other ICS experts, however, said the attackers likely deliberately chose to infect and encrypt the OT network. One of the experts is Nathan Brubaker, who is a senior manager for the cyber physical intelligence team at security firm FireEye. He said that he believes that once the attackers gained initial access, they likely spent days—and possibly longer—using network tools to slowly gain access to more and more of the network. The objective was to carefully explore what resources were connected to it and identify those that were the most mission-critical.

Only after identifying the most critical network resources would attackers run commands that execute the ransomware payload. The technique, known as post-compromise infection, typically encrypts the most valuable resources in the hopes that it will force the victim to pay the ransom.

“Once they do get access, [the attackers] look at who they have access to,” Brubaker told me. “If they get access to a hospital and take down systems critical to the hospital’s operations, the odds of the hospital paying quickly go up. It allows [the attackers] to be a bit more targeted and give more of a return.”

Clint Bodungen, an ICS security expert and founder of the ICS security firm ThreatGEN, agreed. Having done incident response for recent ransomware infections on two oil and gas facilities—one that he believes is the same one described by the Coast Guard and CISA—Bodungen told me:

Ryuk is not an automatic malware. It does not spread by itself. It requires intervention. It requires manual setup and manual deployment. The initial infection was a spear phishing campaign, which was successful, which allows a human actor to reside on the network remotely and remain persistent for several months, the whole time watching, monitoring, and moving laterally throughout the network, eventually taking over active directory systems.

Neither Brubaker nor Bodungen said the attackers intended to cause a catastrophic event. But based on the way Ryuk works—and in Bodungen’s case based on forensics he did on the two hacked oil and gas facilities—both believe the attackers deliberately chose to infect and encrypt the ICS network of the natural gas compression facility.

Ultimately, how concerned should we be about this attack?

Fortunately, the attackers in this compromise didn’t cause any physical damage. But the incident is the latest wakeup call to warn of the potential of hacks that could. (ICS security experts have been sounding these alarms for two decades, so this warning is hardly new.) But since many experts believe this latest attack only unintentionally infected the OT network, many people say the potential danger posed by the incident is being exaggerated.

Bodungen has a different take. He said that because the attackers had manual control and persistence over the network and the HMIs and workstations inside the OT network, the attackers could have taken control of them and done much worse things.

“They absolutely beyond a shadow of a doubt had the foothold capability to do more damage if they had the intent and the knowledge to do so,” he said. “If this keeps up and this level of insecurity remains persistent throughout the industry, at some point, somebody with that intent and that skill level is going to do something. I don’t think it’s an if, it’s a when.”

reader comments

74